Chapter 1 — Legislative Assembly Overview

1.1Indigenous Heritage

The Legislative Assembly and its grounds are located on the homeland of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples, now known as the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations, whose ancestors lived on and cared for these lands for thousands of years.

Indigenous peoples lived on the land now called British Columbia long before the arrival of Europeans, with their own societies, cultures, territories and laws. Today, there are approximately 200,000 Indigenous people in British Columbia and 198 distinct First Nations, each with their own history. Their unique cultural traditions, spiritual beliefs, languages and governance systems continue to shape our province today.

The Legislative Assembly respectfully acknowledges the rich history and enduring wisdom of British Columbia’s Indigenous peoples, recognizes the impact of colonialism and its role in systemic oppression and discrimination, and affirms the importance of reconciliation.

The Knowledge Totem on the Legislative Precinct was carved by Coast Salish master carver Cicero August and his sons Darrell and Doug August on the occasion of the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, New Zealand, and to recognize the beginning of Victoria’s role as the host of the 1994 Games.

The Legislative Assembly respectfully acknowledges the rich history and enduring wisdom of British Columbia’s Indigenous peoples, recognizes the impact of colonialism and its role in systemic oppression and discrimination, and affirms the importance of reconciliation.

Erected in front of the Parliament Buildings, the Knowledge Totem’s loon, fisher, bone game player and frog represent lessons of the past and hope for the future.

2Representatives of the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations, including elected and hereditary Chiefs and Elders, frequently attend special events and ceremonies at the Legislative Assembly, graciously sharing their wisdom, culture and traditions.

1.2British Columbia Joins Canada

The European colonization of what would become Canada included the establishment in 1849 of the Colony of Vancouver Island and, in 1858, the mainland Colony of British Columbia. In 1866, the united Colony of British Columbia amalgamated the two previous colonies.

Canada initially consisted of the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The preamble and section 146 of the Constitution Act, 1867 (previously known as the British North America Act, 1867) contemplated the admission of the Colony of British Columbia and other colonies into the Canadian federation.

In accordance with the procedure for admission in section 146, following requests by the Parliament of Canada and the Legislature of the Colony of British Columbia, B.C. was admitted into Canada on July 20, 1871, through the British Columbia Terms of Union, a May 16, 1871, United Kingdom Order in Council. Section 10 of the British Columbia Terms of Union made the provisions of the British North America Act, 1867 apply in British Columbia as “one of the provinces originally united” in Canada.

The Legislative Assembly of British Columbia met for the first time on February 15, 1872, when the 25 Members elected in the first provincial general election, in the fall of 1871, gathered in the capital of Victoria for the opening of the province’s first Parliament.

1.3Constitutional Framework

Over the past century and a half, the Legislative Assembly’s work has changed dramatically, along with the social and economic transformation of the province. The Assembly’s constitutional framework has supported its changing needs and the social and economic challenges of a growing and diverse population.

1.3.1Democracy and the Rule of Law

Democracy and the rule of law are the fundamental principles underlying Canada’s constitution, which includes written constitutional documents and unwritten constitutional conventions.

The province’s founding constitutional document is the British North America Act, 1867, which was adopted by the United Kingdom Parliament on March 29, 1867, and brought into force on July 1, 1867, creating the Dominion of Canada. The Act establishes Canada as a parliamentary democracy, a constitutional monarchy and a federation, with separate executive, legislative and judicial powers at the federal and provincial levels.

Known today as the Constitution Act, 1867, the Act supports the principle of democracy by requiring the regular election of Members of federal and provincial legislative bodies. It provides for the operation of democracy by instituting federal and provincial Legislatures and empowering them to enact laws in their respective areas of responsibility. In Canada, all government spending requires parliamentary approval. The Act also requires that each legislative body “elect One of its Members to be Speaker” (s. 44), “elect another of its Members to act as Speaker” in the absence of the Speaker (s. 47), ensure a quorum of Members for the conduct of business (s. 48), and make decisions by a majority of Members other than the Speaker, who only votes in case of a tie (s. 49).

Democracy and the rule of law are the fundamental principles underlying Canada’s Constitution.

Under the Act, the Senate and the House of Commons of Canada are authorized to define their privileges, immunities and powers subject to the limit of those held by the United Kingdom House of Commons in 1867 (s. 18). The Supreme Court of Canada has affirmed that this constitutional authority extends to the Legislative Assemblies of the provinces. In New Brunswick Broadcasting Co. v. N.S. [1993] 1 S.C.R. 319, the Court noted:

…the preamble to the Constitution Act, 1867…proclaims an intention to establish “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.” This preamble constitutionally guarantees the continuance of Parliamentary governance and, given Canadian federalism, this guarantee extends to the provincial legislatures in the same manner as to the federal Parliament. The Constitution of the United Kingdom recognized certain privileges in the British Parliament. Since the Canadian legislative bodies were modelled on the Parliamentary system of the United Kingdom, they possess similar, although not necessarily identical, powers. (pp. 5-6).

Provincial Legislatures have confirmed these privileges for themselves. In British Columbia, the provincial Constitution Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 66, s. 50) authorizes the Legislative Assembly to “define the privileges, immunities and powers to be held, enjoyed and exercised by the Legislative Assembly and by the members of the Legislative Assembly.” The Legislative Assembly Privilege Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 259, s. 1) defines those privileges as “the privileges, immunities and powers that were held and exercised by the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom and its committees and members on February 14, 1871, so far as not inconsistent with the Constitution Act….” Further information on these privileges is outlined in Chapter 17 (Parliamentary Privilege).

In 1982, the U.K. Parliament adopted the Canada Act, which abolished the U.K.’s authority over the British North America Act, 1867, renamed it the Constitution Act, 1867, and enacted new provisions in the Constitution Act, 1982, declaring that the Constitution 4 of Canada is “the supreme law of Canada” and incorporating the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, guarantees for Aboriginal rights and procedures to amend constitutional provisions.

Canada’s constitutional provisions are set out in general terms, which has enabled each parliamentary jurisdiction to tailor more detailed laws, rules and practices to regulate its own proceedings in order to suit its particular requirements.

1.3.2Responsible Government

The preamble to the Constitution Act, 1867 declares the intention for Canada of a constitution “similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.” In B.C., responsible government was not fully established until the province joined Confederation. In addition to the provisions set out in written constitutional documents, Canada adopted the constitutional convention of “responsible government” from the United Kingdom. House of Commons Procedure and Practice explains:

Responsible government has long been considered an essential element of government based on the Westminster model. Despite its wide acceptance as being a cornerstone of the Canadian system of government, there are different meanings attached to the term “responsible government”. In a general sense, responsible government means that a government must be responsive to its citizens, that it must operate responsibly (that is, be well organized in developing and implementing policy) and that its Ministers must be accountable or responsible to Parliament. Whereas the first two meanings may be regarded as the ends of responsible government, the latter meaning — the accountability of Ministers — may be regarded as the device for achieving it. (3rd ed., p. 30).

In this system of responsible government, executive authority is carried out in the name of the Sovereign at the federal level by the Governor General, and provincially by Lieutenant Governors, and is exercised on the advice of the jurisdiction’s First Minister, commonly known at the provincial level as the Premier. A list of Premiers of British Columbia is provided in Appendix G. The Premier and Ministers — known formally as the Executive Council and more commonly as Cabinet — are traditionally Members of their jurisdiction’s legislative body and are answerable individually and collectively to that body. In each body, the First Minister must have the support of a majority of Members to control the body’s business and continue in office (see House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 30-1).

Responsible government means that a Premier and Cabinet hold office as long as they have the support of a majority of the Legislative Assembly’s Members and are answerable to the elected Assembly for government policies, programs, decisions and expenditure of public money.

5Parliamentary Procedure in Quebec describes the United Kingdom parliamentary system as having “a ‘soft’ separation of the branches of government, particularly the legislative and executive branches: both Parliament and the governing party participate in legislative functions, which is why constitutional mechanisms fostering or imposing cooperation between them are necessary. These include mechanisms for maintaining contact, exercising oversight and imposing constraints” (3rd ed., p. 48).

1.3.3A Flexible Framework for the Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly’s statutory framework includes the provincial Constitution Act, which was adopted by the Legislature of the Colony of British Columbia in 1871 prior to the province’s admission to Canada. The Act replaced the colonial Legislative Council, which was made up of elected and unelected Members, with a Legislative Assembly consisting of 25 elected Members, and set out rules for government and legislative institutions. The Act has been updated since then. In 2001, the Act was amended to provide set dates for general elections on the second Tuesday in May every four years. This date was changed in 2017 to the third Saturday in October every four years.

The Legislative Assembly and its Members exercise powers and responsibilities provided by the Legislative Assembly Privilege Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 259), the Members’ Conflict of Interest Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 287), the Members’ Remuneration and Pensions Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 257) and the Legislative Assembly Management Committee Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 258). These enactments are outlined in more detail in this book.

1.3.4Role of the Lieutenant Governor

The Constitution Act, 1867 recognizes government authority as “vested in the Queen,” with the Governor General “carrying on the Government of Canada on behalf of and in the Name of the Queen” (ss. 9, 10). At the provincial level, this responsibility is assigned to Lieutenant Governors. The collective term “the Crown” commonly refers to all persons who act on behalf of and in the name of the Sovereign. By constitutional convention, the Governor General and Lieutenant Governors generally act on the advice of the Prime Minister and Premiers, respectively.

British Columbia’s Lieutenant Governor is appointed by the Governor General, acting by and with the advice of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada under the Great Seal of Canada. The Governor General, acting by and with the advice of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada, may appoint an Administrator to execute the office and functions of Lieutenant Governor in the event of an absence, illness or other inability (Constitution Act, 1867, ss. 58, 67). A December 15, 2017 federal Order in Council provided for the “generic” appointment of an Administrator in the absence of B.C.’s Lieutenant Governor to cover a range of situations (authorizing the Chief Justice of British Columbia or, if that individual is unavailable, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, the Associate Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia or 6 another member of the judiciary designated by precedence set out in the Order in Council). This Order represents a move away from a case-by-case appointment. A list of the province’s Lieutenant Governors is provided in Appendix D.

The Lieutenant Governor performs several functions that relate to the Legislative Assembly. Under the Constitution Act, 1867 and the provincial Constitution Act, the Legislative Assembly is summoned, prorogued and dissolved by the Lieutenant Governor, acting on the advice of the Premier. At the opening of a new Parliament, the Lieutenant Governor informs the Members of the Legislative Assembly, through a message read by the Attorney General, of their obligation to elect a Speaker before proceeding to business. The Lieutenant Governor also delivers the Speech from the Throne, outlining the government’s legislative agenda at the opening of each new Session of Parliament.

Under federal and provincial constitutional provisions, a Royal Recommendation must accompany any bill for the appropriation of any part of the public revenue or for any tax. In usual B.C. practice, the responsible Minister advises the Legislative Assembly of the recommendation prior to the introduction of a government bill; the text of the recommendation, more commonly known as a “message,” is then read by the Speaker. The requirement for a Royal Recommendation is outlined in more detail in Chapter 12 (Financial Procedures). Following the Legislative Assembly’s adoption of a bill, the Lieutenant Governor signifies Royal Assent of the bill, which is the final stage in the legislative process for that bill (Constitution Act, 1867, ss. 53, 54, 55; provincial Constitution Act ss. 5, 21, 23, 47). Further information is outlined in Chapter 10 (Legislative Process).

1.4Government and the Confidence Convention

In B.C.’s system of responsible government, executive authority is administered by the party leader who has the support, or confidence, of a majority of the Members of the Legislative Assembly. This is commonly called the “confidence convention.” Constitutional conventions are rules for determining how the discretionary powers of the Crown (or of Ministers, who serve at the pleasure of the Crown) ought to be exercised. The party leader with the backing of a majority of the Members of the Legislative Assembly is normally asked by the Lieutenant Governor to form a government by taking office as Premier and recommending the appointment of other Members to compose an Executive Council, or Cabinet, and serve as Ministers. This applies whether the Premier leads a political party with a majority of Members — a “majority government” or a “coalition government” — or has the support of a majority of Members representing more than one political party — a “minority government.” B.C. has had both majority and minority governments since becoming a province.

Votes of confidence traditionally include votes on the motions for the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, the provincial budget, supply and other votes the government declares to be matters of confidence. Should such a vote be lost by the 7 government, it is normally expected to resign or request through the Premier that the Legislative Assembly be dissolved in order for a provincial general election to be held. As a result, the Legislative Assembly provides for the formation of a government, and its ongoing confidence is required to sustain a minority or a majority government in office. The determination of confidence in the government is a political matter; as noted in Beauchesne, it “is not a question of procedure or order, and does not involve the interpretive responsibility of the Speaker” (6th ed., §168, p. 49; see also House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 41-3).

1.5Functions of the Legislative Assembly

The following functions of the Legislative Assembly are based on constitutional and statutory obligations, as well as the evolving requirements of its Members. Similar functions have been described by other parliamentary jurisdictions (see Erskine May, 25th ed., §§11.1-11.3, pp. 209-10; §11.8, pp. 212-3; House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 23-4).

The Legislative Assembly’s functions include accountability and oversight of government, making laws, authorizing public expenditures and taxation, and representative roles.

1.5.1Accountability and Oversight of Government

The Legislative Assembly’s processes provide forums to hold the Premier and Ministers to account for government policies, actions, decisions and program administration. This includes debates on the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, on the provincial budget, on the granting of authority to spend public funds or administer taxes and on proposed legislation, as well as opportunities to ask questions of the Premier and Ministers during Oral Question Period.

These processes include opportunities to display and confirm the continued confidence of the Legislative Assembly in the government of the day, such as votes on the annual provincial budget and the granting of financial authority in the Estimates.

Like other jurisdictions, the Legislative Assembly supplements its accountability and oversight function through a well-established all-party parliamentary committee system. The membership of parliamentary committees traditionally reflects all political parties officially represented in the Assembly, and may also include Independent Members. Their smaller size provides forums which often take a collaborative approach to the conduct of inquiries and the development of conclusions and recommendations. Parliamentary committees are able to gather evidence from government witnesses as well as external experts or stakeholders. They also enable Members to “take Parliament 8 to the people” and seek public input on important issues through direct consultation with communities and individual British Columbians across the province.

Matters may be referred to parliamentary committees by the Legislative Assembly in accordance with statutory provisions — such as annual budget consultations required under the Budget Transparency and Accountability Act (S.B.C. 2000, c. 23); the scrutiny of reports of the Auditor General under the Auditor General Act (S.B.C. 2003, c. 2); the appointment of statutory officers under enabling legislation for their offices; and the review of statutory provisions as mandated in various acts, such as the Personal Information Protection Act (S.B.C. 2003, c. 63, s. 59), the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 165, s. 80) and the Police Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 367, ss. 38.13, 40.1, 46, 51.2).

1.5.2Making Laws

The provisions of the Constitution Act, 1867, which are mirrored within the provincial Constitution Act, empower the Legislative Assembly to make laws in areas within its provincial jurisdiction. Under the Constitution Act, 1982, laws must also be consistent with the obligations of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and guarantees for Aboriginal rights (s. 35). The law-making function is usually the Assembly’s most time-consuming activity during sessional periods.

As noted, after a proposed law has been considered and adopted in accordance with the Assembly’s rules and procedures, it is presented to the Lieutenant Governor for Royal Assent. Once a bill receives Royal Assent, it becomes an act. The act comes into force upon receiving Royal Assent, if no date of commencement is provided for in the act. Alternatively, the act provides that provisions come into force on one or more dates to be set by an Order of the Lieutenant Governor in Council. Further information is outlined in Chapter 10 (Legislative Process).

1.5.3Authorizing Public Expenditures and Taxes

A fundamental principle of parliamentary democracy is that all expenditures and taxes must be authorized by a jurisdiction’s elected representatives. To this end, the Constitution Act, 1867 provides that only provincial Legislatures can authorize public expenditures and taxes within their jurisdictions.

As stated previously, financial legislation must be accompanied by a Royal Recommendation from the Lieutenant Governor, which is obtained on the advice of the Executive Council. These provisions are also reflected in Standing Orders 66 and 67. The government has the right to initiate financial and tax measures, but the Assembly must authorize such measures through the adoption of legislation. Assembly procedures for this authorization provide Members with opportunities to scrutinize financial initiatives and hold government to account regarding proposed new expenditures and taxes. Further information is outlined in Chapter 12 (Financial Procedures).

91.5.4Representative Roles

The Legislative Assembly provides Members with opportunities to represent the specific concerns of individual British Columbians and constituents. These opportunities include daily periods for two-minute Statements by Private Members when the Assembly is sitting. Members may also raise issues important to them and their constituents during debates on the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, the provincial budget, legislation and the Estimates, as well as during Oral Question Period and Private Members’ Time on Monday morning sittings. Outside of formal proceedings, Members may contact Ministers or their officials about policy or program matters affecting individual citizens. The Assembly supports Members in establishing constituency offices which provide services to constituents who have questions or concerns about, or require assistance with, provincial government policies, programs and benefits.

The representative work of Members may include some or all of the following responsibilities. House of Commons Procedure and Practice notes:

They act as ombudsmen by providing information to constituents and resolving problems. They act as legislators by either initiating bills of their own or proposing amendments to government and other Members’ bills. They develop specialized knowledge in one or more of the policy areas dealt with by Parliament, and propose recommendations to the government. They represent the Parliament of Canada at home and abroad by participating in international conferences and official visits. (3rd ed., p. 216).

Individual British Columbians or groups may also communicate to Parliament by way of petitions, which are a request for action by the Legislative Assembly. Petitions must be presented to the Legislative Assembly by an elected Member, and are further outlined in Chapter 15 (Public Petitions).

1.6Political Parties, Government and the Opposition

Political parties are an important element of our modern-day institution, but this was not always the case in British Columbia. From 1871 to 1903, governments depended on informal agreements and coalitions of Members which were subject to shifts in personal allegiances. The development of political parties in B.C. responded to this political instability, the challenge of mobilizing rising numbers of voters in a growing population, and the need for legislators to manage increasingly complex social and economic issues (see Canadian Provincial Politics, 2nd ed., pp. 42-3). In advance of the 1903 provincial general election, The Daily Colonist suggested that “the introduction of party lines into provincial politics is at once inevitable and desirable…because it guarantees, as nothing else can, stable and responsible government” (September 14, 1902, p. 4). In the ensuing election, Sir Richard McBride became the first B.C. Premier to be 10 elected with a declared political party affiliation in 1903 (see Electoral History of British Columbia 1971-1986, p. 6).

Although political parties are not mentioned in constitutional statutes, they are a component of other statutes. For example, the provincial Election Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 106) authorizes the registration of political parties; regulates their financing and the financing of political party leadership contests, the endorsement of electoral candidates by registered political parties, the informing of electors about this endorsement, and reporting to the Legislative Assembly of the individuals elected to serve as Members; and provides for an annual allowance to registered political parties whose candidates in the most recent provincial general election received at least 2 percent of the total votes in all electoral districts, or at least 5 percent of the votes cast in districts where the party endorsed candidates. The determination of political party leaders is a matter for the political parties themselves.

The Members of the Legislative Assembly usually serve as Members of the government caucus or an opposition caucus based on their political party affiliation.

Most Members of the Legislative Assembly serve as Members of the government caucus or an opposition caucus, based on their political party affiliation. The opposition may be comprised of the Official Opposition Caucus, as well as any other recognized opposition caucuses and Independent Members. Officially recognized political party caucuses qualify for funding to carry out their parliamentary duties and activities. Such funding is administered pursuant to the Legislative Assembly Management Committee Act (R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 258, s. 3) by the Legislative Assembly Management Committee.

1.6.1Government

As noted, under the system of responsible government, the leader who has the confidence of a majority of Members, regardless of whether there is a minority or majority government situation, is invited by the Lieutenant Governor to form a government and serve as Premier. The continued confidence of a majority of the Assembly’s Members is required for a government to remain in office. The Premier advises the Lieutenant Governor to appoint Members to serve as Ministers in an Executive Council, including the Premier, who serves as President of the Executive Council. The Premier and Ministers carry out the administration of government and are accountable to the Assembly for their decisions and actions.

Responsible government and parliamentary democracy can function whether the Premier leads a political party with a majority of seats in the Assembly or in a minority government situation, where the majority of Members may come from more than one political party, or with the support of Independent Members. Three general 11 approaches to governing are possible in minority situations. First, in ad hoc or informal arrangements, a majority of votes is secured on an informal or case-by-case basis — e.g., the 1952-53 B.C. minority government, or the 2004-2011 Canadian, 2011-14 Ontario and 2007-08 and 2012-14 Quebec minority governments. Second, with formal political agreements, two or more parties agree to form a combined majority on specific issues — such as the 2017 Confidence and Supply Agreement between the B.C. New Democratic Party Caucus and the B.C. Green Party Caucus, or the 1985 Accord between the Ontario Liberal Party and the Ontario New Democratic Party. Third, in coalition governments, Cabinet positions are shared among two or more parties — which is rare in the Canadian experience (see House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 39-40; 49-53).

The leader of a political party who has the confidence of a majority of Members is invited by the Lieutenant Governor to form a government.

1.6.2Ministerial Responsibility

In our system of responsible government, ministerial responsibility takes two forms: individual responsibility and collective responsibility. Ministers are individually accountable to the Legislative Assembly for carrying out statutory duties, actions and decisions as well as other administrative responsibilities assigned by the Premier. Ministers are collectively responsible for carrying out government’s policies as decided by the Executive Council, also known as Cabinet solidarity. Consequently, once a decision has been made by the Executive Council, it is supported publicly by all Ministers (see House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 30-1).

In the Legislative Assembly, collective ministerial responsibility is demonstrated through solidarity in votes on the motions regarding the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, the provincial budget, as well as government motions and government legislation. A government motion standing in the name of a Minister may be moved by any Minister, in accordance with the practice which permits Ministers to act for each other on the grounds of the collective nature of government. It is also a long-established principle that the decision on the transfer of questions (e.g., during Oral Question Period) rests with Ministers and is not a matter in which the Speaker seeks to intervene (see Erskine May, 25th ed., §22.9, p. 520).

1.6.3Opposition

Responsible government provides that the Premier and Ministers are accountable to the Legislative Assembly. Opposition Members play a key role in holding the government to account for their decisions and actions. A list of Leaders of the Official Opposition and Leaders of the Third Party is provided in Appendix H.

12Opposition Members play a key role in holding the government to account for its decisions and actions.

1.6.3.1Official Opposition

By convention, the opposition party with the most seats in the Legislative Assembly is designated as the Official Opposition, and its leader is recognized as the Leader of the Official Opposition. The Official Opposition is generally the largest minority group in a Parliament which plays an important role in the parliamentary system and has received practical recognition in the procedures of parliamentary institutions. Tradition and the Standing Orders accord the Official Opposition with precedence over other recognized opposition parties. In addition to scrutiny of government actions, decisions and expenditures, the Official Opposition may provide alternative policies and proposals, and is sometimes referred to as a “government in waiting.”

1.6.3.2Third Parties and Other Opposition Parties

The provincial Constitution Act defines the “leader of a recognized political party” as the leader of “an affiliation of electors comprised in a political organization…that is represented in the Legislative Assembly by two or more Members” (s. 1). In 2017, this threshold was reduced from four seats to two by an amendment to the provincial Constitution Act. Third parties and other opposition parties have been recognized in the Legislative Assembly from time to time, most recently in the 41st Parliament, following the 2017 provincial general election, and in the 35th Parliament, following the 1991 provincial general election.

1.6.3.3Independent Members

Independent Members include Members without political party affiliation and those who are not part of a recognized political party caucus.

1.6.3.4Opposition Critics

Traditionally, opposition party leaders assign Members of their respective parties to serve as “critics,” or lead caucus spokespersons, in specific policy areas, in order to monitor government initiatives, question government and outline alternative policies (see Erskine May, 25th ed., §4.6, pp. 47-8). These positions do not receive additional remuneration.

1.6.4House Leaders, Caucus Whips and Caucus Chairs

Like in other Westminster jurisdictions, B.C. political party caucuses have established positions to coordinate their activities in parliamentary proceedings. These positions include House Leaders, Caucus Whips and Caucus Chairs. The Government and Official Opposition Whips may be assisted by Deputy Caucus Whips (see Erskine May, 25th ed., §4.7, pp. 48-9; §4.9, pp. 50-1; House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 33-5).

13Their significant parliamentary responsibilities are recognized in the Members’ Remuneration and Pensions Act (s. 4), which provides remuneration for these positions and other parliamentary roles.

1.6.5House Leaders

Recognized party caucuses appoint a House Leader to support the leader with the development of the party’s parliamentary strategy and operations.

The Government House Leader is most commonly a senior Minister to whom the Premier assigns responsibility for the oversight and timing of government’s legislative program and other government business in the Legislative Assembly. The Government House Leader normally advises all Members of the government’s plans for government business when the Assembly reaches Orders of the Day at each sitting.

The Government House Leader’s prerogative over government business in the Legislative Assembly is established in procedure and practice. The Government House Leader has unique responsibilities and powers to plan and manage the business of the government in the Legislative Assembly and in Committees of the Whole and the Committee of Supply. In order to minimize conflicts on procedural matters, including scheduling of Assembly business, a consultative process is recommended and often utilized to support a practical and efficient management of legislative business during a sessional period, consistent with Practice Recommendation 6. However, it is recognized that consultations may not always produce a consensus in a collective parliamentary environment, and, as such, the government may avail itself, particularly when holding majority status, of procedural mechanisms to advance its agenda in the Assembly.

Recognized opposition House Leaders also support their leaders with the coordination of party caucus approaches to Assembly business and procedural matters.

1.6.6Caucus Whips

Government and opposition Caucus Whips are selected by their respective party leaders and perform parliamentary, political and administrative duties for their caucuses. They ensure that their respective caucus Members are present in the Chamber and in committee rooms for parliamentary business and votes. Under Standing Order 25B, Members must notify their Caucus Whip if they wish to make a two-minute Statement during Routine Business. The Whips also assist with Members’ participation in Private Members’ proceedings on Monday mornings by making or responding to a Private Member’s Statement as well as their participation in general debate. As required, Caucus Whips “confer to settle the names of the six Members who will be recognized for ‘Statements,’” as noted in Standing Order 25B. The Caucus Whips also oversee Members’ attendance and coordinate absences. Seating assignments in the Chamber are also typically determined by the Caucus Whip.

141.6.7Caucus Chairs

The Members of recognized political parties meet frequently among themselves to discuss political and policy issues. Caucuses typically meet in camera on a frequent basis when the Legislative Assembly is sitting, and at other times as determined by the party’s leadership. Caucuses may also establish internal committees to deal with specific issues. Government and opposition party Caucus Chairs assist their leaders with the internal coordination of political matters among party Members (see House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., pp. 33-4).

1.6.8Cross-Party Consultation and Legislative Assembly Proceedings

In B.C., consultation among political party caucuses provides a measure of stability to the work of the Legislative Assembly, while maintaining their respective political positions. Through common approaches to votes among their Members, especially votes of confidence, and collaboration on operational matters, political party caucuses can benefit from stability for the ongoing business and functions of the Assembly.

House Leaders and Caucus Whips facilitate discussions among caucuses (and Independent Members) on the day-to-day timing and sequence of parliamentary business in support of the practical and efficient management of Assembly business and procedural matters.

The House Leaders and the Caucus Whips of recognized political parties facilitate discussions amongst caucuses (and, as required, Independent Members) on the day-to-day timing and sequence of parliamentary business in support of the practical and efficient management of Assembly business and procedural matters. For example, it has long been recognized that agreement on the allocation of time under Standing Order 81.1, reached as the result of consultations, may be announced by the Government House Leader, and that agreements as a result of consultations between the Government House Leader and opposition parties may curtail dissent with respect to the moving of motions related to Assembly business (see Erskine May, 25th ed., §§4.5-4.9, pp. 47-51; House of Commons Procedure and Practice, 3rd ed., p. 34).

Collaboration amongst House Leaders and Caucus Whips is also significant for the Assembly’s financial and administrative management. The Legislative Assembly Management Committee Act provides a forum for collaboration across all political parties represented in the Assembly by requiring membership including the government “Minister” (in recent practice, the Government Whip has served in this role); Government and Official Opposition House Leaders and Caucus Chairs; and a Member from any other recognized political party; and, where such an appointment is needed, the appointment of an additional Government Caucus Member.

151.7Parliament Buildings

The Legislative Assembly Management Committee Act (s. 1) defines the “Legislative Precinct” as the area encompassing the Parliament Buildings, the legislative grounds and Confederation Garden Park, other buildings in Victoria occupied by the Assembly’s Members and staff and other land or buildings or both, other than constituency offices, designated by minute of the Committee. Under the Act (s. 1), the “legislative grounds” consists of the area bounded by Belleville, Menzies, Superior and Government Streets. The Legislative Precinct has served as a site of government in B.C. since 1864.

Figure 1-1: Main Parliament Buildings

British Columbia’s iconic Parliament Buildings are the Legislative Assembly’s main physical building. The Parliament Buildings include the Legislative Chamber, meeting rooms and office and support accommodations for all Members of the Legislative Assembly, their staff and Assembly officials. Designed by architect Francis Rattenbury and built under the Parliament Buildings Construction Act, 1893 (S.B.C. 1893, c. 34), the Parliament Buildings were officially opened on February 10, 1898. They replaced colonial buildings known as the “Birdcages,” which had housed the Legislature of the Colony of Vancouver Island and continued to be used by the Legislative Assembly after British Columbia became a province of Canada in 1871. The southern wing for the Legislative Library was completed in 1915 and formally opened on March 2, 1916.

Since 1898, the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia has been housed in the Parliament Buildings.

As noted, the Legislative Precinct is located on the traditional territories of the Lekwungen-speaking people, now known as the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations. On November 18, 2006, the Governments of Canada and British Columbia signed land settlement agreements with the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations respecting a parcel of land in downtown Victoria, including the grounds of the Legislative Assembly.

16The Speaker is responsible for accommodation and services on the Legislative Precinct in view of the Legislative Assembly’s statutory right to administer its own affairs free from interference, including areas required for official parliamentary functions. Under the Legislative Assembly Management Committee Act (ss. 1, 4), the Speaker holds administrative responsibilities including the provision of security within the Legislative Precinct and its management and use by Members, staff and the public.

The legislative grounds are frequently used for public gatherings, including special events, celebrations marking B.C. Day and Canada Day, and demonstrations and marches on matters of public interest. The Speaker regularly grants permission for use of the legislative grounds to the public for non-commercial events — including performances by choirs and bands and the taking of wedding photographs — following the review of an application and subject to compliance with guidelines established by the Legislative Assembly.

1.7.1Seating in the Chamber

The Legislative Chamber has seating for all Members of the Legislative Assembly. The Speaker occupies a raised chair at the south end of the Chamber. By tradition, Members of the Government Caucus sit to the right of the Speaker, and Members of any opposition caucus sit to the left, depending on the number of Members in each recognized caucus. The Leader of the Official Opposition and other Members of the Official Opposition sit opposite the Premier and members of the Executive Council.

The Clerk of the Legislative Assembly and Assembly procedural advisers, known as Table Officers or Clerks, are provided with three seats at a Table in front of the Speaker’s chair.

1.7.2Bar of the House

The Bar of the House is a long brass rod which marks the boundary of the Legislative Chamber beyond which visitors may not pass while the Assembly is sitting. The Sergeant-at-Arms is provided with a seat inside the Chamber near the Bar.

The Legislative Assembly historically called individuals to the Bar on occasion to admonish them; more recently, the Assembly has invited individuals to the Bar in order to pay tribute to them. For example, on December 2, 1998, Chief Joe Gosnell of the Nisga’a Nation addressed the Assembly from the Bar of the House on the matter of the Nisga’a final agreement with the Government of Canada and the Government of British Columbia (see B.C. Journals, December 2, 1998, p. 181); on October 15, 2007, Chief Kim Baird of the Tsawwassen First Nation addressed the Assembly regarding the Tsawwassen First Nation agreement (see B.C. Journals, October 15, 2007, p. 123); and on February 14, 2013, Tla’amin First Nation Chief Clint Williams addressed the Assembly on the Tla’amin First Nation agreement (see B.C. Journals, February 14, 2013, p. 15).

17

Figure 1-2: Bar of the House

1.7.3Public Galleries and Legislative Press Gallery

The Public Galleries and Press Gallery above the Chamber provide seating for public visitors, the Legislative Press Gallery and distinguished visitors. The Press Gallery seats are directly behind the Speaker so that, in keeping with parliamentary tradition, they are not within the Speaker’s view. These journalists and media representatives are the only guests in the galleries who are permitted to take notes. Coats, briefcases, backpacks, cameras and electronic devices are not permitted, and photography, reading and note-taking are not allowed. The Sergeant-at-Arms, supported by gallery staff, is responsible for preserving order in the galleries.

1.8Parliamentary Symbols

The Legislative Assembly has adopted symbols and practices from Westminster and Indigenous traditions to honour and respect the breadth of our province’s history.

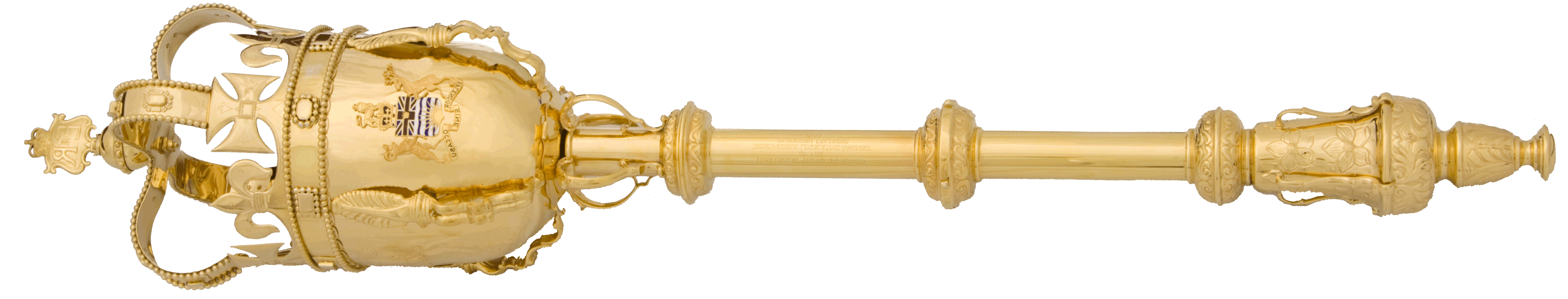

181.8.1Mace

The Mace is a symbol of the authority of the Legislative Assembly and the Speaker. Used in many jurisdictions, it dates back to the 13th century in England as a symbol of royal authority received by the House of Commons.

The Legislative Assembly has adopted symbols and practices from Westminster and Indigenous traditions to honour and respect the breadth of our province’s history.

In B.C. practice, the Sergeant-at-Arms carries the Mace to lead the Speaker’s Procession at the opening and closing of each sitting, and places it upon the Table when the Assembly conducts its business. During the election of a Speaker, the Mace is placed in the lower cradle on the Table; after the Speaker is elected, the Mace is placed upon the Table. When the Speaker leaves the Chair for the Assembly to go into a Committee of the Whole, the Mace is also placed in the lower cradle on the Table to indicate that the Speaker is no longer presiding over the Assembly. The Mace is not present when the Lieutenant Governor is in the Assembly.

Figure 1-3: Mace

Since 1871, there have been three Maces in the Legislative Assembly. The first, used from 1872 to 1897, was made of gilded carved wood. The second, used from 1898 to 1953, was made of brass. The current Mace, in use since 1954, was handmade by Victoria silversmiths from B.C. silver and is plated with gold. It features a shaft topped by a bowl bearing the coats of arms of Canada and B.C. and scenes of the province’s forestry, fishing, farming and mining industries, which are similar to murals featured in the upper Memorial Rotunda of the Parliament Buildings.

191.8.2Black Rod

The Black Rod was inaugurated in 2012 as a ceremonial staff to be used on formal occasions when the Sovereign or the Lieutenant Governor is present in the Legislative Chamber.

Created to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, the Black Rod comprises a shaft made of wood from seven B.C. trees, a silver replica of the St. Edward’s Crown (a symbol of the monarchy), a Canadian diamond and an engraving of the Pacific Dogwood, the provincial flower.

The mid-section features a carving in jade, B.C.’s official gemstone, by Tsimshian Elder Clifford Bolton (Soō—Natz) depicting a man, woman and child. The man and woman are joined together by two eagle feathers, sacred Indigenous symbols of power. The child symbolizes hope for the future. A carved cedar rope signifies unity and the intertwining of the diverse cultures of the province.

Four silver rings near the base of the Black Rod include three dating to 2012 inscribed with the national motto of Canada, the B.C. provincial motto, and the motto of the Order of the Garter. The fourth ring, called the Ring of Reconciliation, was affixed in 2016, containing a motto in the Halq’eméylem language — Lets’e Mot, meaning “one mind” — marking a step toward reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Figure 1-4: Black Rod

1.8.3Talking Stick

In 2016, a Talking Stick became the most recent symbol at the Legislative Assembly. Talking Sticks are traditionally used during potlatch ceremonies on the west coast of British Columbia, and are a powerful symbol and communication tool used to foster an atmosphere of active listening and respect.

In 2010, the late Chief Robert Sam of the Songhees Nation gifted the Talking Stick to the Honourable Steven Point, then the province’s Lieutenant Governor, who presented it to his successor, the Honourable Judith Guichon, with a request that it be given to the Speaker and put on display in the Legislative Chamber.

20

Figure 1-5: Talking Stick

In 2016, the Talking Stick was presented to Speaker Reid, who accepted it on behalf of all Members, at a special blessing ceremony, and placed in the Chamber. The Talking Stick remains on display in the Chamber, adjacent to the Speaker’s chair, to serve as a symbol of mutual respect and as a reminder that reconciliation should be a consideration in all debates and discussions in the Legislative Assembly.

1.9Statutory Officers

The Legislative Assembly has adopted legislation to create nine statutory officer positions, and their offices generally support the work of Members in holding the government to account. The officers are accountable to the Legislative Assembly and report to the Assembly on their responsibilities.

The following independent statutory officer positions have been established in British Columbia: the Auditor General, the Chief Electoral Officer, the Ombudsperson, the Conflict of Interest Commissioner, the Human Rights Commissioner, the Information and Privacy Commissioner and Registrar of Lobbyists, the Police Complaint Commissioner, the Merit Commissioner and the Representative for Children and Youth. Each fulfills the responsibilities assigned to them in the statutory provisions that govern their work.

While eight statutory officers are officers of the Legislature, the Conflict of Interest Commissioner is an officer of the Legislative Assembly, meaning that the incumbent fulfills the unique responsibilities of that office in support of Members and on behalf of the Legislative Assembly.

Statutory frameworks ensure the operational independence of these officers. Over the years, these frameworks have evolved to include the following elements for independence: appointment based on the unanimous recommendation of an all-party parliamentary committee and approval by the Legislative Assembly; statutory mandates; authority to establish offices and hire staff; and review by the Assembly — not the government — of budgetary estimates to fund an independent office’s operations and staffing for each fiscal year.

The operational independence of statutory officers is balanced by an ongoing legislative oversight relationship with the Legislative Assembly. To this end, their statutory frameworks also include reporting to the Assembly through the Speaker on issues within their mandates and the 21 review of statutory office financial plans, priorities and budgets by the Legislative Assembly, work that is typically undertaken by a parliamentary committee.

The operational independence of statutory officers is balanced by an ongoing legislative oversight relationship with the Legislative Assembly.

Since 2001, the Select Standing Committee on Finance and Government Services has exercised legislative oversight of the officers with its annual financial review of statutory office budgets, annual reports and service plans and has provided guidance on general administrative matters and workplans. In addition, the audit reports of the Office of the Auditor General are presented in the Assembly and most are referred for consideration to the Select Standing Committee on Public Accounts, while the reports of the Representative for Children and Youth are presented and referred for review to the Select Standing Committee on Children and Youth.

Information on the work of B.C.’s statutory offices and their reports to the Legislative Assembly are available on the websites of individual statutory offices.